Cloud Repatriation: When Leaving the Public Cloud Actually Makes Sense

Pro Tips

Jan 26, 2026

Public cloud changed how infrastructure teams build and ship. It removed a lot of upfront friction, made experimentation cheap, and let small teams run systems that once required a data center and a large staff.

None of that stopped being true. But as systems mature, more teams start to question whether running everything in the cloud still makes sense. Traffic becomes easier to predict. Latency starts to matter more. And finance begins asking harder questions about costs.

That’s usually when cloud repatriation enters the conversation. This guide is meant for technical leaders who want a practical way to think through that decision, without guessing or making a move they regret.

What “cloud repatriation” means in practice

Cloud repatriation is moving selected workloads out of a public cloud and running them somewhere else: bare metal, colocation, private cloud, or a hybrid blend of all of the above.

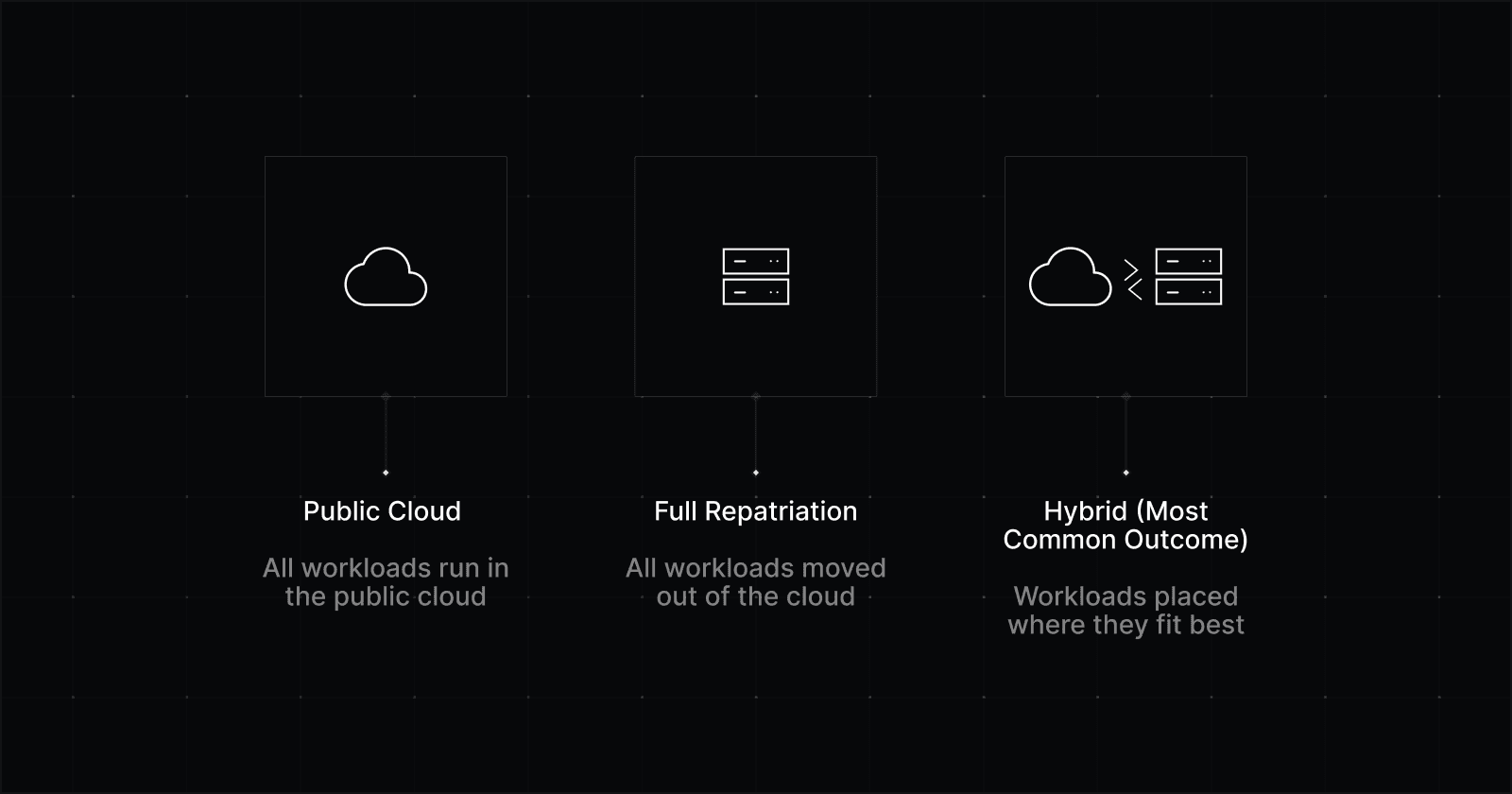

A recent report found that 87% of qualified decision-makers expect to pursue some form of repatriation within the next two years. Yet, only 18% plan to fully repatriate all public cloud workloads over the next two years.

Mature setups trend toward hybrid solutions because different workloads have different needs. Some systems want elasticity and managed services. Others want predictable cost and performance.

The good news: You can have both, if you design for it.

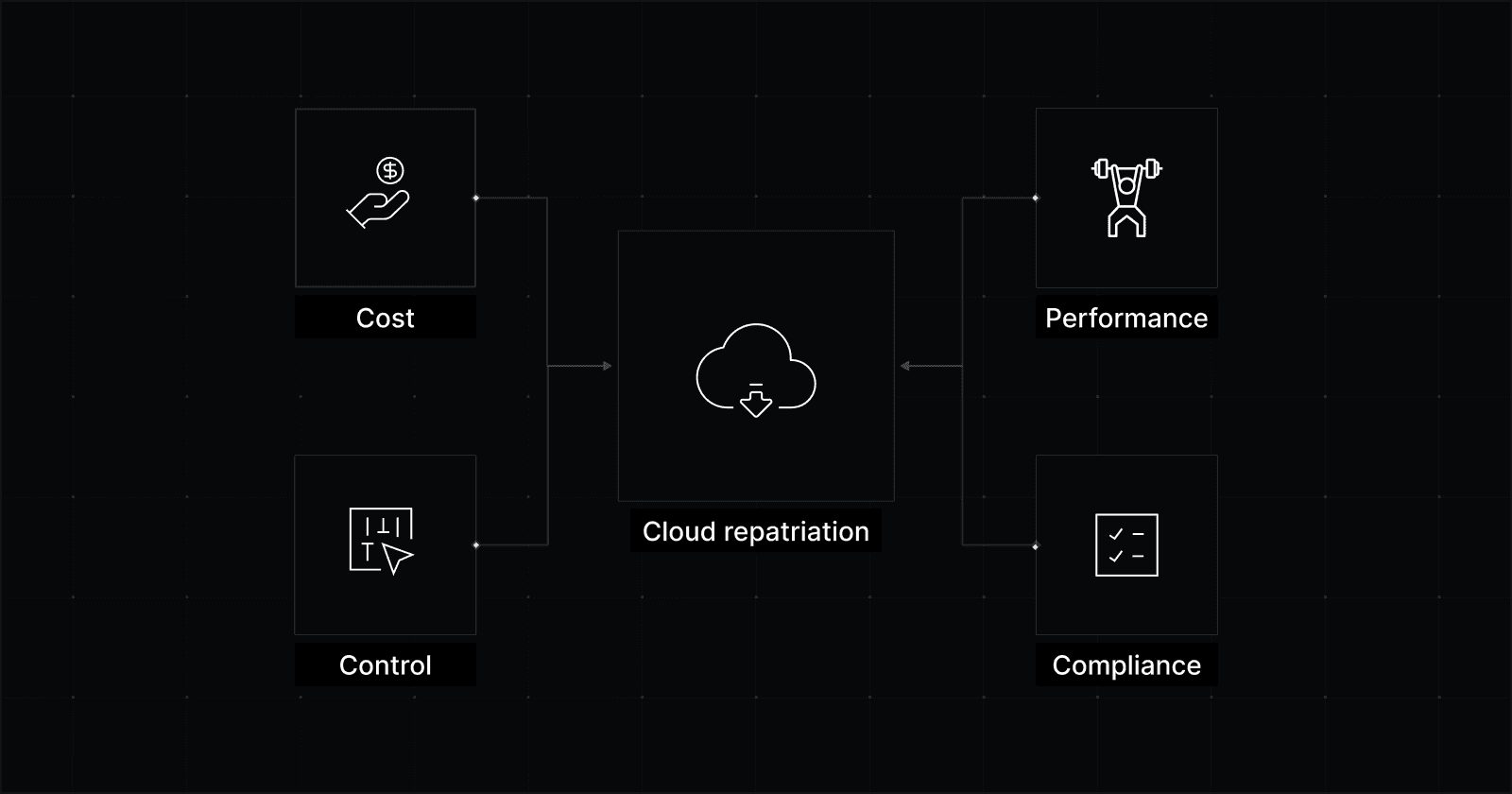

When and why teams rethink their public cloud assumptions

Cloud exit conversations usually start when the bill jumps or performance problems get too loud to ignore.

But once teams investigate, they often realize it’s not a one-off mistake or a temporary misconfiguration. They discover it’s the public cloud business model doing what it’s designed to do, and their workload has grown into the part that gets taxed the hardest.

When they reach this point, teams usually try to optimize their cloud resources. They might explore AI tools and services designed to reduce inefficiencies. While this can help, it doesn’t solve the underlying problem. As the workload grows, the same issues keep coming back.

1. The “elastic pricing” model stops making sense once the workload is predictable

Public cloud pricing favors elasticity: scale up, scale down, pay for what you use.

That is great for:

Spiky traffic

Jobs that run in periodic bursts

Experiments

Dev and test environments

Anything with unclear or changing requirements

It’s a weaker fit for the core services that run all day, every day with little variation, like databases, queues, caches, API backends, and background jobs.

Over time, teams realize they are paying a premium per unit for flexibility they rarely use. If a workload is “always on” and its capacity plan is predictable, you’re renting flexibility that you aren’t using.

That doesn’t automatically mean you should move it. But it does suggest that the financial downside of staying in the cloud is no longer justified by “because we might need to scale tomorrow.”

Cloud promises “infinite” scale. This means there’s always petabytes and petabytes of idle capacity with public clouds to support bursts. These idle resources still take up space and power and therefore must be budgeted for by cloud providers.

2. Egress quietly becomes one of your biggest cost drivers

When it comes to the cloud, sending data in is free. Sending it out comes at a cost. This is how cloud platforms try to lock you in and where they pick up their margin.

For services that send a lot of data out, the cost keeps going up in a straight line: more use means more data goes out, which means a bigger bill.

Some workloads feel this pain more than others:

SaaS & fintech platforms serving large API responses to users, partners, or integrations

Adtech & analytics teams exporting event data, logs, or datasets to customers and BI tools

Media, gaming, and marketplaces delivering video, images, or downloadable assets at scale

AI & data companies syncing models, embeddings, or training data across regions or clouds

Multi-region products replicating databases and storage for redundancy or portability

3. Performance spikes become a real problem

Multi-tenant environments like public cloud share physical resources.

Even with good isolation, you still live near other tenants. Shared NICs, shared storage, virtualization layers, and oversubscription all show up as performance variance.

Your averages can look fine on a dashboard. P95 and P99 are where the real issues show up. Early on, those occasional spikes are easier to live with. The system is still changing fast, and you haven’t locked in tight expectations yet.

But when a system matures, variability becomes expensive, triggering incidents, eating away at user trust, and burning time on debugging sessions.

4. Compliance is rarely “done” after you pass an audit

Some teams mistakenly think of compliance as a one-time checkbox.

In reality, it’s an ongoing responsibility that shows up in everyday things like where data lives, who can access it, how it’s protected, and whether you can prove all of that when asked.

Public cloud platforms can support compliant workloads, and many do. Because some responsibilities sit with the provider and others sit with your team, audits often take longer and require more explanation.

Dedicated infrastructure can simplify things. When hardware, networks, and access boundaries are dedicated to a single customer, ownership is clearer and control is easier to demonstrate.

For organizations operating under regulatory scrutiny, that clarity can matter more than a long list of certifications.

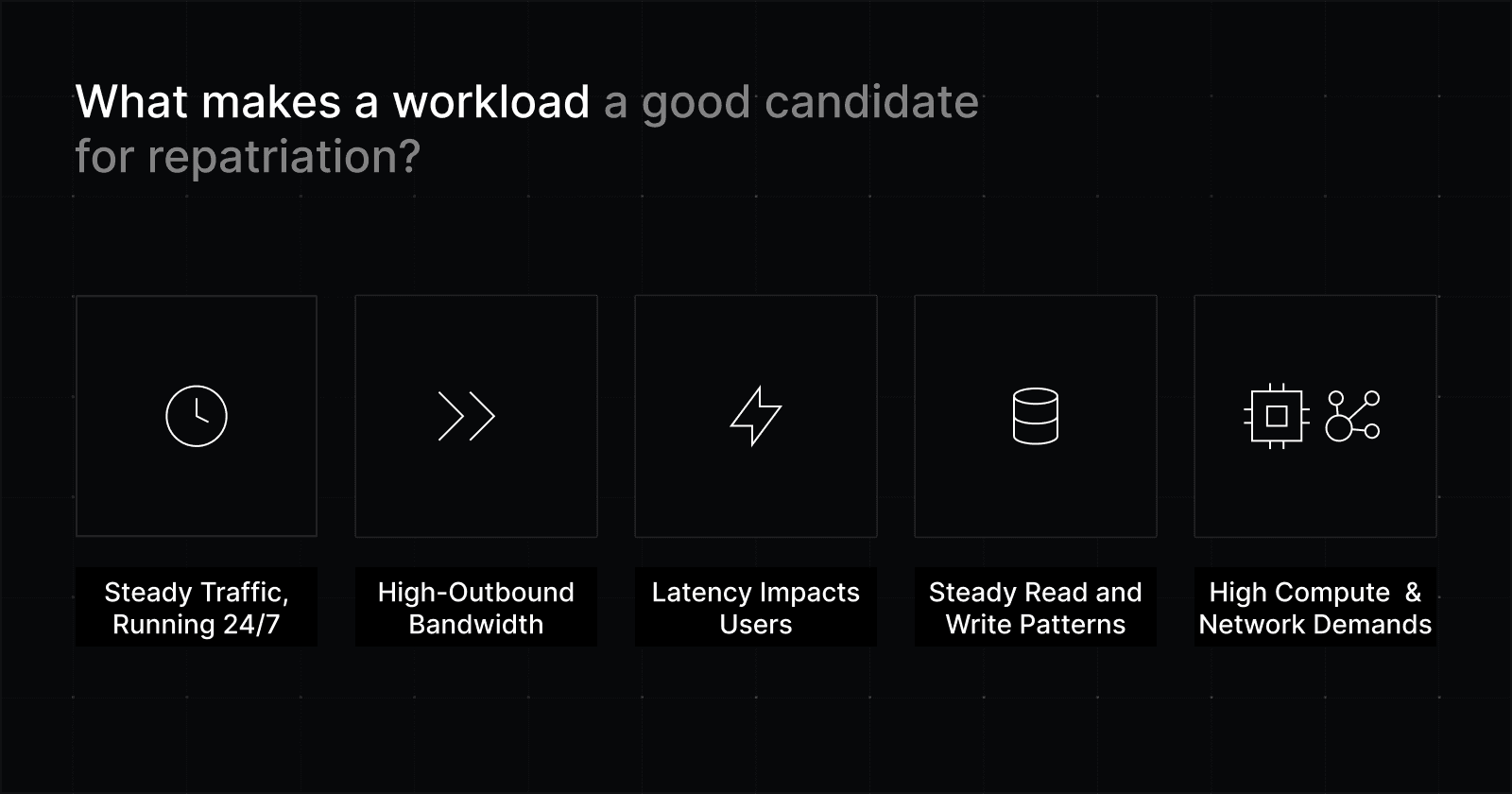

Which workloads are good candidates for repatriation?

When considering a move off the cloud, it’s important your team starts with the right question.

The question isn’t: “Should our company exit the cloud?”

It’s: “Which workloads are wrongfully paying the cloud tax?”

That way of thinking can be the difference between a smooth migration and a headache.

Strong signals a workload should be reconsidered

Look for workloads with some combination of:

Saas backends that run 24/7 with steady traffic and predictable usage

Adtech, gaming, or content services consuming high-outbound bandwidth

Trading, real-time analytics, and multiplayer/live systems where latency directly impacts users

Databases with steady read and write patterns

AI, data, or infra-heavy services that need fast CPU, NVMe, or high-throughput networking.

Sometimes the issue at hand is performance (keeping P95 and P99 in bounds). Sometimes it’s cost (bandwidth and always-on capacity that never really turns off). Often it’s both.

Once a workload starts behaving this way, the next question is whether it’s also predictable. That’s usually what determines whether other infrastructure options make sense.

If you can project capacity needs for the next 6–12 months, you can stop renting “maybe” and start buying for the reality you have. That’s where non-cloud pricing models tend to win.

If you can’t, cloud might still be the right place to pay for uncertainty.

Workloads that usually belong in public cloud

Some workloads are better off in the cloud:

Spiky or seasonal workloads where elasticity is expected

Short-lived dev and test environments

Systems that rely heavily on managed cloud services (i.e. databases)

Workloads run by teams without experience operating infrastructure

That last point is especially important. Running dedicated infrastructure can add new responsibilities for your team, depending on what your provider manages for you.

If the tradeoff is saving money in exchange for more operational risk, that risk can grow quickly without the right people, processes, and experience.

The hidden risk you should know: vendor lock-in

Managed services can be very helpful. They save time and let teams move faster.

The downside is that many of these services are hard to leave. That’s usually by design, since it helps the provider keep customers.

You don’t notice this when things are going well. It shows up when prices change, contracts come up for renewal, or something stops working. That’s often when teams realize they’re more stuck than they expected.

That’s no reason to avoid managed services altogether. It means you should treat vendor lock-in as a real risk, not something to be surprised by later. If a service is worth using, that’s fine. Just make sure you understand what it would take to leave before you’re under pressure.

For any managed service that becomes critical, it helps to write a one-page exit plan that answers these questions:

How do we get our data out?

What data needs to be exported, in what format, and using which tools or APIs?What would replace this service?

Is there a clear alternative, whether another provider or an in-house option?How long would the move realistically take?

Think in weeks or months, not best-case scenarios.What breaks or degrades during the transition?

Performance, features, automation, or operational visibility often take a hit during a move.

If you can’t answer these questions clearly, that tells you something important. It means you’re more dependent on the service than you thought.

It’s much better to learn that early, when you have time and people available, than during an outage or an argument over a surprise bill.

How to plan a cloud exit without guesswork

Good cloud exits usually look boring from the outside. That’s a good thing.

A little upfront work can save you months of work, surprise costs, and a migration you wish you hadn’t started.

Step 1: Map inventory and dependencies

Start by documenting:

Workloads

Dependencies (data, network, auth, service-to-service calls)

Data gravity (what data lives where, how it moves)

Network flows (including cross-region or cross-account traffic)

Failure domains and blast radius

This is where “simple” systems often turn out to be more complicated than you thought. Many repatriation problems come from realizing too late that the cloud was doing more behind the scenes for a workload than it seemed.

Don’t forget to map egress early. Teams tend to underestimate how much data crosses paid boundaries, especially between services. |

|---|

Step 2: Model 12–36 month total cost of ownership

Don’t treat this as a month-to-month bill comparison. That can hide costs that only show up once a system has been running for a while.

Total cost of ownership is about what it really takes to run a workload over time, not just what shows up on this month’s invoice. It includes the obvious costs, the ongoing work, and the risks you take on by running the system yourself.

To get a realistic picture, model costs over 12 to 36 months. That should include:

Compute, or the servers you need to run the workload

Storage, including backups and snapshots

Bandwidth, including replication, cross-region traffic, and third-party services

Labor, both to build the system and to keep it running

Migration work, since engineering time isn’t free

Risk costs, like downtime or the effort needed to roll back a bad change

Contract exit costs, if you have them

Use conservative assumptions. Plans that rely on best-case scenarios tend to break as soon as reality shows up.

As a rule of thumb, expect to spend more time than you think on the boring but necessary work: access controls, monitoring, patching, backups, certificates, identity systems, and runbooks. That work is part of owning infrastructure, whether it’s visible on a bill or not.

Step 3: Test before you move

The safest migrations keep an easy way back for as long as possible. Instead of a big switch all at once, use tests that let you learn without locking yourself in:

Parallel runs

Canary workloads

Shadow reads

Replication to the new environment before cutover

Clear rollback procedures

You don’t need to be an expert in all of these techniques to get the point.

All it means is make small, low-risk moves first. Try things out. Keep the old system running while you learn how the new one behaves. And make sure you can switch back if something doesn’t work.

Step 4: Choose your provider carefully

A smart cloud exit focuses on reducing costs without taking on unnecessary operational work. The goal is to keep the speed and tools you liked about cloud, while removing the costs and constraints that stopped making sense for your system.

When evaluating dedicated infrastructure providers, focus on a few key things:

Predictable pricing

Especially for bandwidth. If traffic matters to your business, costs shouldn’t spike unexpectedly. Look for clear pricing that won’t punish growth.A cloud-native workflow

You should be able to provision and manage infrastructure through APIs and automation. If everything requires clicking around in a dashboard, things slow down quickly.Hands-on migration help

Providers should be able to help plan the move and explain how to roll back if something goes wrong.Operational guardrails

You need reliable access, clear boundaries for failures, built-in redundancy, and support that responds when things break. The system should be easy to troubleshoot under pressure.Managed operations, if you want them

Some teams move off cloud to simplify, not to take on more work. Make sure “fully managed” actually means timely support from real engineers, not slow ticketing.

If a provider can’t give clear answers on these points, a cloud exit that looks good on paper can easily turn into a headache.

Those priorities reflect how Rackdog approaches our infrastructure options for teams moving off the cloud.

When repatriation is the wrong move

Moving off the cloud isn’t always the right answer. In some cases, it creates more problems than it solves.

Repatriation is usually the wrong move when:

The workload is highly elastic or unpredictable

The team isn’t ready to run infrastructure day to day

A managed service delivers more value than its lock-in cost

The migration risk outweighs the expected savings

Restraint is a sign of good judgment. Not every expensive cloud bill is a signal to leave.

Sometimes the better move is to improve the architecture, optimize the workload, or accept that cloud flexibility is still doing real work for you.

Final takeaway

Public cloud is a useful tool. Dedicated infrastructure is a useful tool. Private cloud and colocation can be useful too. Most mature teams end up using a mix, depending on the workload.

What matters is understanding how your workloads actually behave and choosing the model that gives you the most leverage. That usually comes down to balancing cost, performance requirements, and what your team can realistically support. Planning ahead can help you weigh the pros and cons and make a smarter decision in the long run.

If bare metal is on your list as you rethink performance or cloud costs, our team can help you assess whether it’s a good fit. At Rackdog, we’ve helped companies across a range of sizes and industries improve performance, regain control, and make infrastructure costs more predictable.

Up next

Basics

Feb 2026

What Is a Bare Metal Server?

Get a clear explanation of what a bare metal servers is, what makes them different from cloud, and key advantages and disadvantages of running workloads on bare metal.

Read

Jan 2026

Introducing the Next Chapter of Rackdog

8,000 bare metal and 12 global locations later, we’re starting the next chapter of Rackdog with a new brand, a redesigned website, and a platform built around how modern teams deploy, scale, and operate infrastructure every day.

Read